For the rare and radiant maiden […]

Nameless here for evermore.

– ‘The Raven’, Edgar Allen Poe

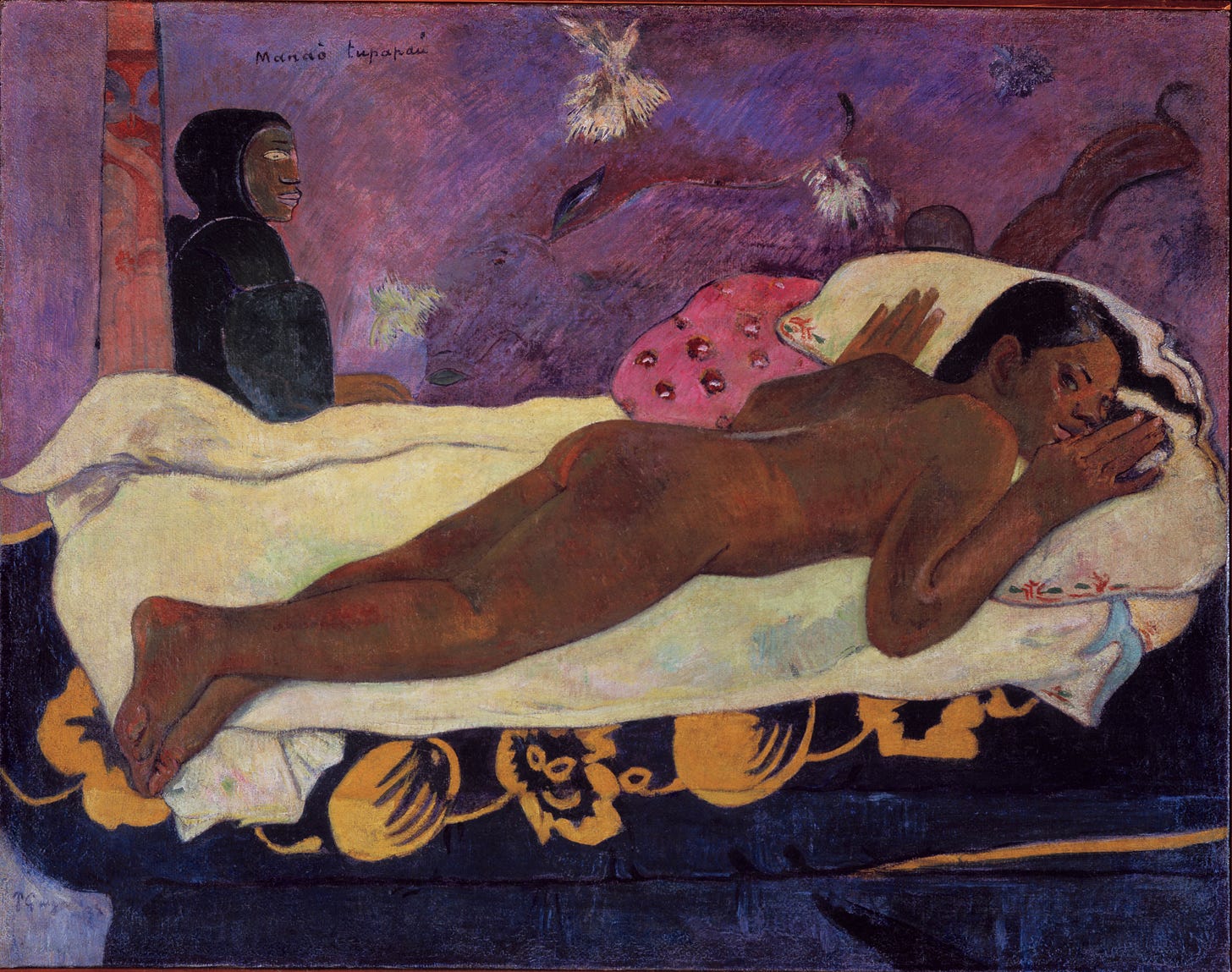

There’s a painting at the Courtauld Gallery here in London I like a lot, which I’m sharing here in the hope that a personal blog falls under the remit of non-commercial use. It’s a Gauguin from 1897, painted in Tahiti during his second and final stint on the island. It’s titled Nevermore, and if you’ve spotted the raven, yes, like that nevermore.

The painting is a riff on a traditional reclining nude (think her, her, her) and depicts a Tahitian woman lying on her side. But unlike these women, who incline themselves outward, often gazing directly at the viewer, Nevermore’s subject is a closed figure, curled slightly in on herself and looking back into the scene – either at the raven perched on the windowsill or at the two figures standing just outside the door. It gives the impression of a girl alone, perhaps in trouble, abandoned. The raven is abstracted but sinister, while the figures in the background feel protective – either of the girl herself or what the girl threatens. They appear to me as women talking, bringing to mind a community network of female voices that intervene when formal structures fail.

I initially read this painting as a young, pregnant girl whose lover had abandoned her, forcing a community reckoning, or at least gossip. (This reading is not entirely out of line with the reality of Gauguin’s life in Tahiti, but more on that later.) The Courtauld curators interpret the work as expressing Gauguin’s ‘disillusionment at the destruction of Tahitian culture’ by the French colonial presence and increasing Europeanisation of what he had previously experienced as an ‘unspoilt’ island paradise. Of course, Gauguin himself had a hand in that destruction – as a French man living in Tahiti, he necessarily polluted the ‘purity’ of the island, which in his idyllic fantasy wouldn’t have any French people living on it. He used the island to his own ends, his relative wealth allowing him a life and reputation otherwise inaccessible to him in France.

Claire Dederer is more explicit in Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma,

Gauguin […] abandoned his wife and children to flee to Tahiti, where he didn’t know the language or the religion or the customs, none of which prevented him from sleeping with young Tahitian girls, an act of sexual colonisation that he himself was only too happy to mythologize.

In feminist criticism, the female body is often read as representing geography or land. We call countries ‘motherlands’, a place can help raise us, the contours of a woman’s body look like the natural curves of a landscape, there are parallels of fertility – you get the idea. From that vantage point, the woman in the painting becomes a metaphor for Tahiti itself: taken over and exploited by the people who ostensibly love her, and abandoned after the shine has worn off and her resources used up.

Nevermore is a classic example of the colonial, sexual gaze we’ve come to associate with Gauguin’s work: the painting depicts a young woman whose appeal depends on her exoticism and the access she gives to an ‘uncivilised’ space. But despite this, the subject gives off an air of being fed up, looking back over her shoulder in irritation through the layers of narrative that don’t belong to her. The thing that’s most interesting to me about this painting is that Gauguin both reveals his worldview and indicts it in the same stroke of the brush – and given what I’ve learned about Gauguin in researching this essay, it seems unlikely he did that on purpose.

The fed up girl at the centre of Nevermore is Pau’ura, who became Gauguin’s ‘wife’ in Tahiti when she was just 14. Pau’ura was actually Gauguin’s second wife of this kind, as he had ‘married’ a 13 year old girl called Teha’amana when he first came to Tahiti in 1891.

In 1893, Gauguin quit Tahiti in favour of Paris, leaving behind Teha’amana and their son. When that didn’t work out and he returned to the island two years later, Teha’amana wanted nothing to do with him (obviously). So he had to find somebody else.

Enter Pau’ura.

According to Bengt Danielsson, author of Gauguin in the South Seas, Pau’ura

was in every respect inferior to Teha’amana, the general consensus of opinion (which included Gauguin’s) being that she was stupid, lazy, and slovenly. There was another important difference […]: Pau’ura was not so dependant on him for company as Teha’amana had been.

Teha’amana, whose ‘marriage’ to Gauguin had been arranged and executed in a single afternoon, had always been seen an outsider. As a result, she was in Gauguin’s thrall: he offered her security and a place to belong. Comparing Nevermore to an analogous, earlier painting of Teha’amana – Spirit of the Dead Watching – reflects the stark difference between the two women in Gauguin’s imagination.

Unlike Pau’ura, Teha’amana poses an inviting figure, subdued but emotionally engaged with the viewer. She is gazing outward, while the warm colour scheme and tactility of the bed linens draw you in. This depiction is consistent with what she represented to Gauguin: the newness and innocence of Tahiti (ripe for the taking!) and the sweetness of his early life there. As Devika Ponnambalam writes, ‘she was unspoilt by progress and his first perfect muse’.

In contrast (scroll up, lol), Nevermore has a cool, greenish colour scheme that seems to place it in a separate space from the viewer. This effect is magnified by the depth of the painting – much of the action goes on behind the figure, while in Spirit of the Dead Watching, the space behind the figure seems flat, with the room reaching outward toward you. The woman in Nevermore is clearly disengaged, and while we can see more of her body, her arms and legs curl forward around her torso in a protective, standoffish position.

Likewise, Pau’ura, in comparison to Teha’amana, was not an ‘unspoilt’ muse – she mostly seemed to like Gauguin for his money. At one point, Pau’ura temporarily left him, but didn’t seem to see the break in their relationship as a reason to stop taking things from his house, leading him to set the police after her. Their relationship finally ended when she refused to move with Gauguin to another part of the island, further from her family. According to Danielsson, Gauguin was fairly relaxed about leaving her behind, along with their two-year-old son. (If child-abandonment was a sport, this guy would be in the Olympics, that’s all I’m saying.)

It’s in the juxtaposition of Teha’amana and Pau’ura that Gauguin’s references to Edgar Allen Poe begin to make sense.1 Interestingly, Poe also married a 13 year old – his cousin – when he was 26, which seems like a freak coincidence until you read Poe and Gauguin’s work side-by-side. I don’t mean that Gauguin is deliberately drawing attention to his and Poe’s shared… affinities (though Gauguin had previously written a whole book on how cool it was to sleep with Tahitian preteens). Rather, I mean that their respective marriages are a direct byproduct of their sense of the world as corrupted and a fixation on their own loss of innocence, a quality they then attached to young girls and pursued in relationships with them.

We see this thought process illustrated in Poe’s ‘Annabel Lee’. The poem is about the speaker’s dead lover, the aforementioned Annabel Lee, whom he describes in the first stanza as ‘liv[ing] with no other thought | Than to love and be loved by me’. The speaker and Annabel Lee fell in love as children, with a love so pure that it was envied by angels, who – in their jealousy, the speaker claims – called Annabel Lee to a premature death. The speaker remains devoted to Annabel Lee, as he ages and she does not, noting their love

was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we—

Of many far wiser than we.

It’s thought that the inspiration for this poem was Poe’s wife, Virginia, who had recently died at the ripe old age of 24. The poem extols the virtues of an ‘innocent’ love, stronger than the love of adults, in part because of its purity and youth. Annabel Lee’s singleminded purpose is to love the speaker, which is depicted as a product of the quality of her love, and not the fact that she is a… child. Lying beneath the twee, sing-song ABAB stanzas is a sinister undercurrent of an adult man infatuated with a young girl, who represents a holy and unattainable innocence cemented by her death. We don’t know anything about Annabel Lee except that she died young; the only thing we know about the speaker is that he’s still hung-up on his childhood girlfriend, an emotional stuntedness that inspired Vladimir Nabokov in writing Lolita. (Humbert Humbert, Lolita’s paedophilic narrator, points to a childhood romance with a girl named Annabel Leigh as the starting point of his lifelong sexual obsession with children.)

If ‘Annabel Lee’ is Poe’s poem of blissful devotion to his child bride, his more famous ‘The Raven’ transforms this devotion into a haunting. The speaker is visited by a raven, who he believes is a messenger from the afterlife, bringing news of his (again) dead lover, a ‘rare and radiant maiden’ called Lenore. When the raven repeats only, ‘Nevermore’, despite the speaker’s increasingly desperate pleading for news of Lenore, or at the very least distraction from his grief. He tells himself the raven has come to offer ‘respite and nepenthe from thy memories of Lenore’, to which the raven heartlessly replies, ‘Nevermore’. The poem ends with the raven ‘still […] sitting’ on the speaker’s door, casting a shadow over the room:

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted—nevermore!

‘The Raven’ depicts a man driven to madness by the loss of a maiden (read: young) lover, sealed in a hell of knowing he can never reclaim the innocence she represented to him. In titling his painting ‘Nevermore’, Gauguin shows his hand. The raven in the painting casts its shadow over Pau’ura – but Pau’ura is still here, representing in her insolence his failure to reclaim the innocence of Tahitian life and the freshness of his own youth that he projected onto his first wife. Pau’ura doesn’t cooperate with his attempt to start over in Tahiti. She’s too difficult to idealise, and even if she weren’t, she could never take him back to that time of his life anyway. That’s the thing about innocence: you lose it. Eventually, your child wives grow up.

Gauguin is fully aware of what he’s lost and paints a defiant Pau’ura to underline it. She will never be Teha’amana; he will never be young again; Tahiti will never be like it was when he – and all the other Europeans who trampled in – ‘found’ it. What indicts him, though, is how false and frankly twisted what he’s lost is. To the contemporary viewer, the distance and resistance between the subject and the painter in Nevermore feels more correct than the sexuality and strangeness of Spirit of the Dead Watching. Nevermore gives the impression that it’s pushing the artist out the picture, revealing his true nature as an unwelcome voyeur.

The experience Gauguin mourns is revealed to be an experience of his own fantasy and imagination, disconnected from the reality of Tahiti and the lives of the women he tried to co-opt to build his own legend. While an incredible artist, he failed to receive widespread recognition in his lifetime. When his paintings wouldn’t sell, he tried to increase his renown by cultivating an exotic persona through attachments to exotic women (in Tahiti and in France). That he ‘married’ and sexually exploited 13 year old girls in Tahiti was no secret, but rather something he publicised widely through his deliberately shocking memoir, Noa Noa.

So then how do we approach Nevermore as a work? Dismissing it as a work of colonial and sexual exploitation is too simple, and it doesn’t leave space for the fact that, as an artwork, it is undeniably a masterpiece. Moreover, Pau’ura reaches out from the painting, confronting you with her identity, her inability to be tamed. As Ponnambalam writes about Teha’amana, while paintings like Spirit of the Dead Watching and Nevermore ‘are difficult for people to accept today’, the paintings reveal their subjects’ worlds. She continues, ‘Without […] the power that [the painting] exudes, I would never have embarked on a journey to discover [Teha’amana’s] truth and her voice’. Gauguin is behind that power, but his works take on a life beyond him.

Dederer argues that ‘consuming a piece of art is two biographies meeting: the biography of the artist, which might disrupt the consuming of the art; and the biography of the audience member, which might shape the viewing of the art’. In viewing and loving Nevermore, I’d like to layer in a third biography: the biography of the subject, who meets the artist before the work has even begun, and, in this case, adds a complexity, richness and beauty to the work by speaking a truth the artist himself could not have articulated.

Gauguin claimed the poem’s title and depicted raven were not drawn from Poe, but the similarities are too similar to be ignored, especially given his friendship with Édouard Manet, who, among other things, illustrated the French edition of Poe’s poems, translated by Stéphane Mallermé, who read his translation of ‘The Raven’ at Gauguin’s farewell banquet before his first journey to Tahiti (Danielsson).

Maybe my favorite piece you've written on here so far, even though you ruined my birthday buddy Mr E.A.P. for me! Always knew Gaugin was a scumbag, but the dirt on Poe... What is it with horror fantasy writers and degeneracy?

I appreciate how you provide a lens to enable the discerning viewer, reader, etc to revere the art apart from the artist. Your thoughts help clarify mine as I'm writing an essay on Kerouac's On the Road (out next Thursday, only on Substack!). Kerouac himself was probably a racist, almost definitely a misogynist, and certainly lived hedonistically, all of which comes across in his writing...and yet On the Road, while communicating these views on his part, comes across not endorsing them. Just as Gaugin intended with Nevermore to express a self-blind disillusionment with his second child-bride and the corrupting of her culture and yet ended up painting a bit of a self-own, Kerouac--perhaps unintendingly--wrote a book which makes a pretty good case against living like a libertine and showing the realistic detriments of that lifestyle on the women in the focal characters' lives. It's fascinating how scoundrels speak the truth without meaning to.

Good stuff, Hannah!

Thank you for sprinkling my day with art history, poetry, social commentary, and most importantly, that we all exist in a context we can only choose to respond to. Brilliant once again!